Wartime child worker reveals dark secrets of

Japan's "Rabbit Island"

Okunoshima has become famous globally as Japan's Instagrammable "Rabbit Island" but little is known about its dark history as a host to a wartime poison gas factory and weapons plant.

Today, people come to enjoy the picturesque views of the Seto Inland Sea from campgrounds and hiking trails in the Inland Sea National Park, with the island's charm and intriguing past making it a compelling subject for online content.

Eighty years ago, the island hosted a secret poison gas factory that played a key role in Japan's illegal use of chemical weapons in occupied China. It was also a production site for the military's long-range, unmanned, incendiary "balloon bombs" that were used against the United States during World War II.

Reiko Okada was mobilized to the island as a teenager for the war effort, helping the Imperial Japanese Army build balloon bombs known as "Fu-Go."

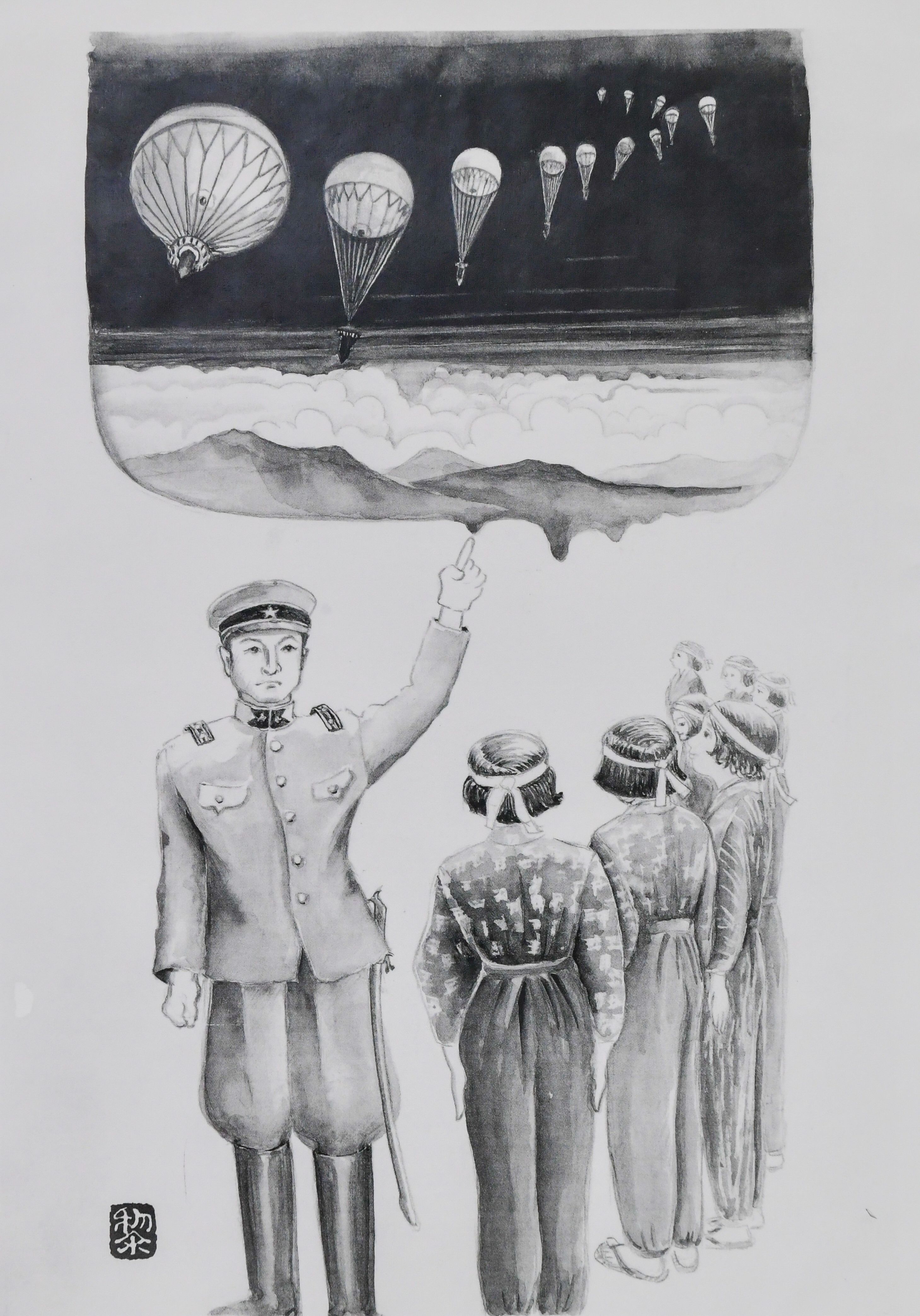

A painting by Reiko Okada depicting mobilized students receiving instructions on how to use "balloon bombs" (Courtesy of Reiko Okada)

A painting by Reiko Okada depicting mobilized students receiving instructions on how to use "balloon bombs" (Courtesy of Reiko Okada)

Okada, now 95, is one of the few people still alive who has both a "gas notebook" for poison gas victims and an "A-bomb notebook" for survivors of the atomic bomb.

Japan, which was a signatory to the Geneva Protocol of 1925 that prohibited the use of chemical and biological weapons, produced mustard gas and other deadly chemical weapons on Okunoshima, at what was the largest poison gas factory in Asia.

The Tadanoumi factory, located on Okunoshima Island in Takehara, Hiroshima Prefecture, where poison gas weapons were manufactured until the end of the war, as seen in a 1946 photo. (Courtesy of Reiko Okada)

The Tadanoumi factory, located on Okunoshima Island in Takehara, Hiroshima Prefecture, where poison gas weapons were manufactured until the end of the war, as seen in a 1946 photo. (Courtesy of Reiko Okada)

Okada was sent to Okunoshima as a 15-year-old third-year student at Tadanoumi Girls' High School in Takehara -- near the seaside Hiroshima Prefecture city located on the main island of Honshu -- in 1945.

Female students from Tadanoumi Girls' High School who participated in Japan's war effort (Courtesy of Reiko Okada)

Female students from Tadanoumi Girls' High School who participated in Japan's war effort (Courtesy of Reiko Okada)

After the United States dropped the atomic bomb on Aug. 6, 1945, effectively bringing about Japan's defeat in World War II, she also worked as a relief worker in the suburbs of Hiroshima.

In an interview, the former art teacher from Mihara, Hiroshima Prefecture, declared her willingness to tell the "last story of my life" and warned: "If we do not face up to our responsibility as perpetrators of the war, we will repeat the mistakes of the past."

At the end of 1944, the government had proclaimed "ichioku gyokusai," translated literally as "100 million shattered jewels." The phrase served as the last unofficial rallying cry of the empire, expressing the regime's willingness to sacrifice the entire Japanese population, if necessary, to protect the fatherland.

Whenever Okada, who was mobilized in November of the same year, heard these words, she stared fixedly at the surrounding waters and thought: "I don't want to die."

The following summer, when Japan was bombed by U.S. air raids in various regions, Okada and the other girls were suddenly ordered to "evacuate" poison gas materials to a neighboring island.

In the sweltering heat, the schoolgirls donned work gloves and transported the chemical barrels to a dock, making more than a dozen trips a day for over two weeks.

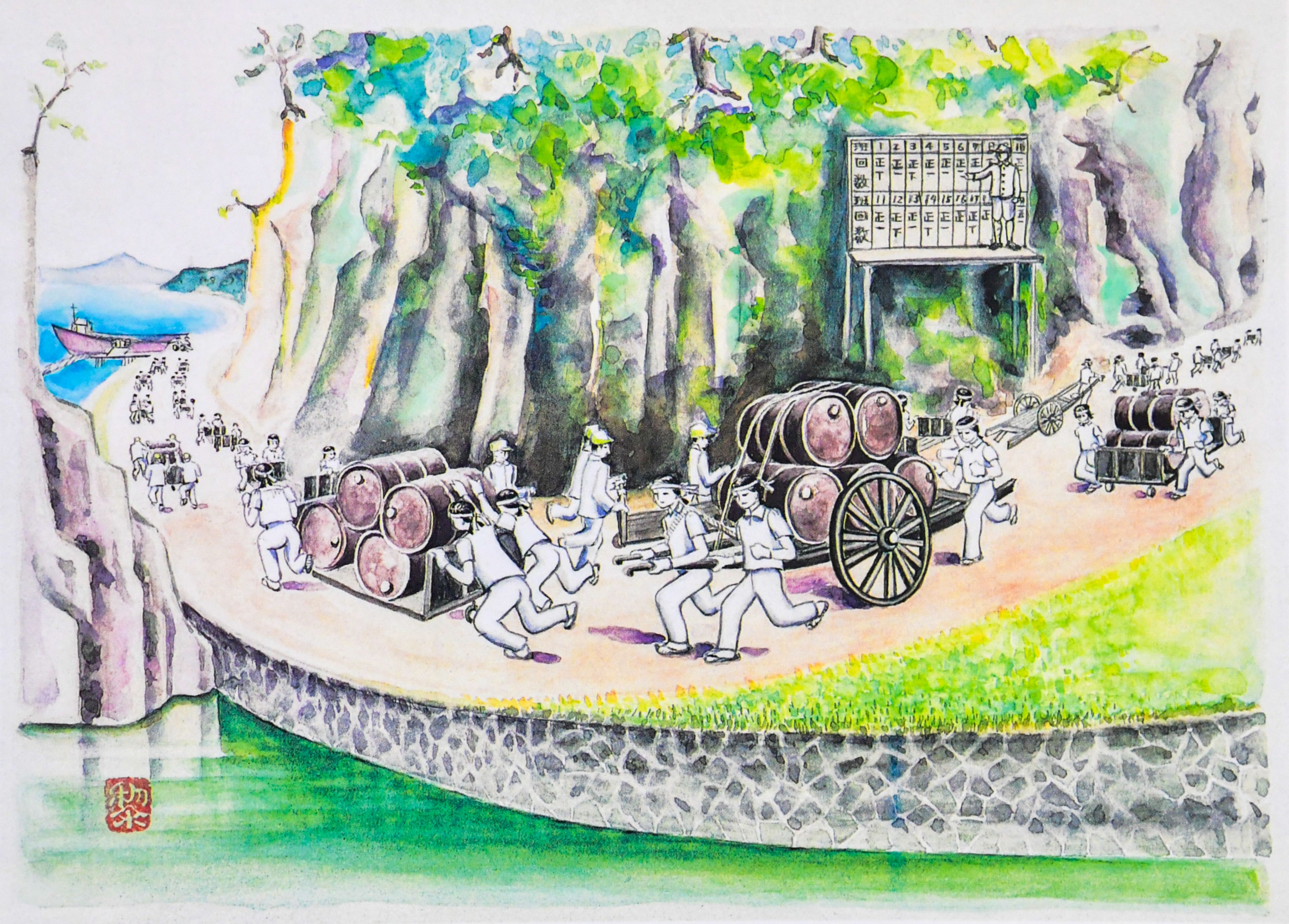

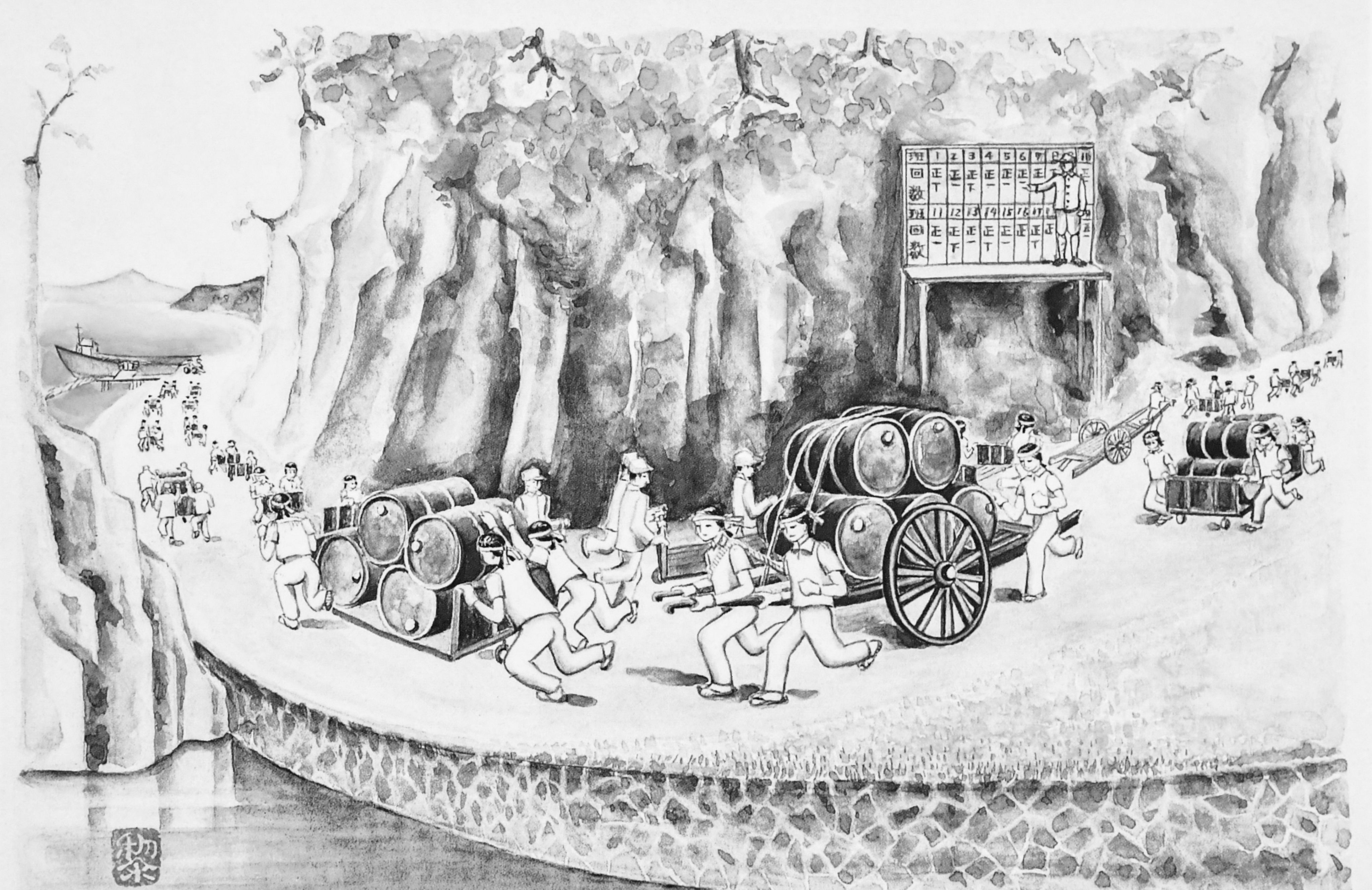

Reiko Okada's painting depicting the "evacuation" of poison gas raw materials to a nearby island by mobilized students (Courtesy of Reiko Okada)

Reiko Okada's painting depicting the "evacuation" of poison gas raw materials to a nearby island by mobilized students (Courtesy of Reiko Okada)

Okada says she and the others were given strict instructions by the army not to reveal Okunoshima's location to family or friends.

People listen to the "Jewel Voice Broadcast," which announced the end of the war on Aug. 15, 1945, in front of a radio.

People listen to the "Jewel Voice Broadcast," which announced the end of the war on Aug. 15, 1945, in front of a radio.

On Aug. 15, students gathered in a square on the island to listen to the "Jewel Voice Broadcast" in which Emperor Hirohito announced Japan's acceptance of the Allied demand for unconditional surrender in a radio address.

Then, for about two weeks from Aug. 18, she was involved in an A-bomb relief effort in a middle school auditorium in a suburb of Hiroshima. She says it was a horrific scene where people were dying every day.

"It felt like a damp world of maggots crawling inside weakened bodies," she recalled.

Okada, who had traveled to the city within two weeks of the bomb's detonation, was certified as a "hibakusha" -- atomic bomb survivor -- because she had entered the affected area shortly after the attack.

Before that traumatizing period, she had spent time on the island in the weapons factory.

There, she and her fellow students used a paste made from konnyaku root to build the unmanned, hydrogen-filled balloon bombs, which were 10 meters in diameter and made of Japanese washi paper.

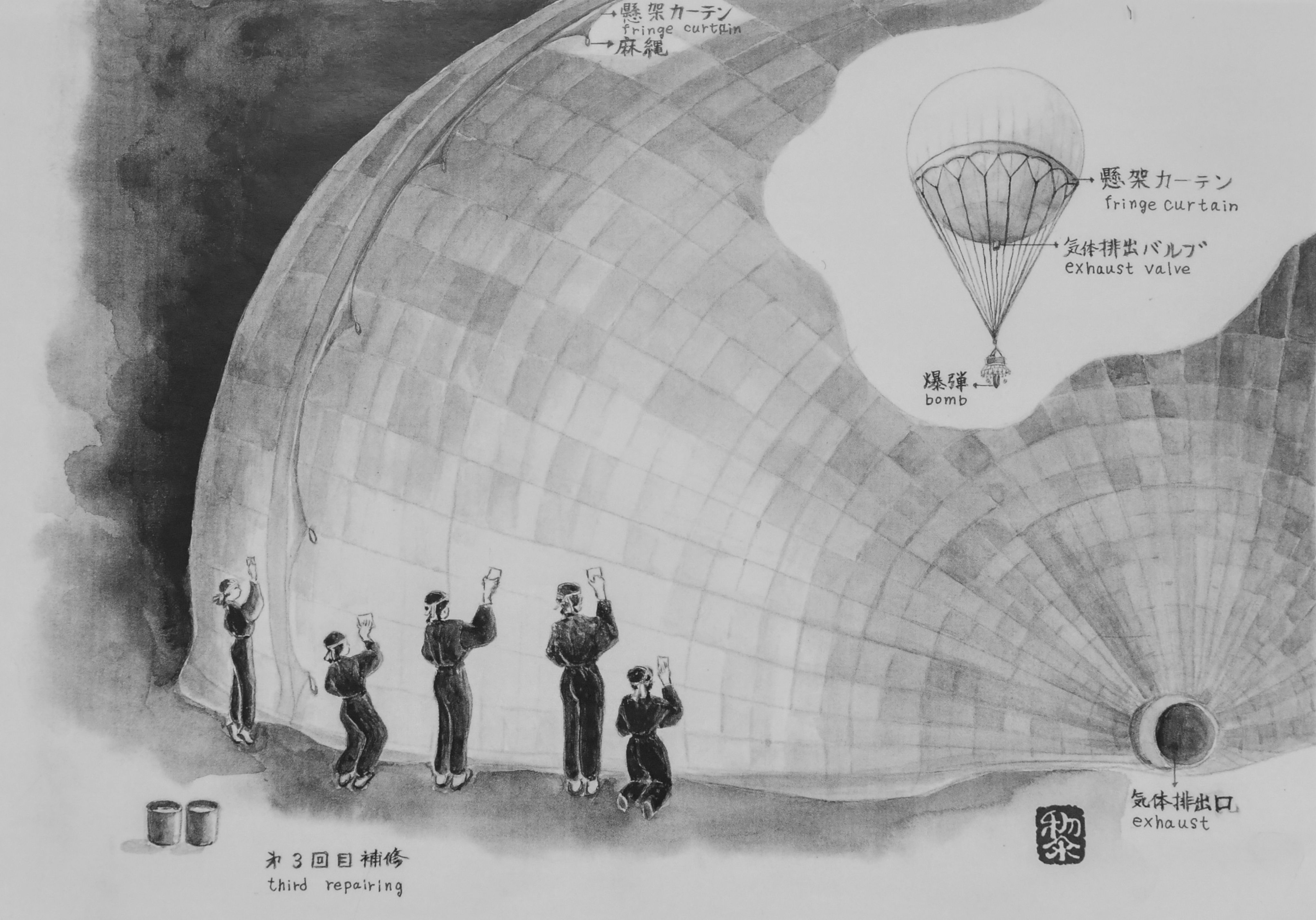

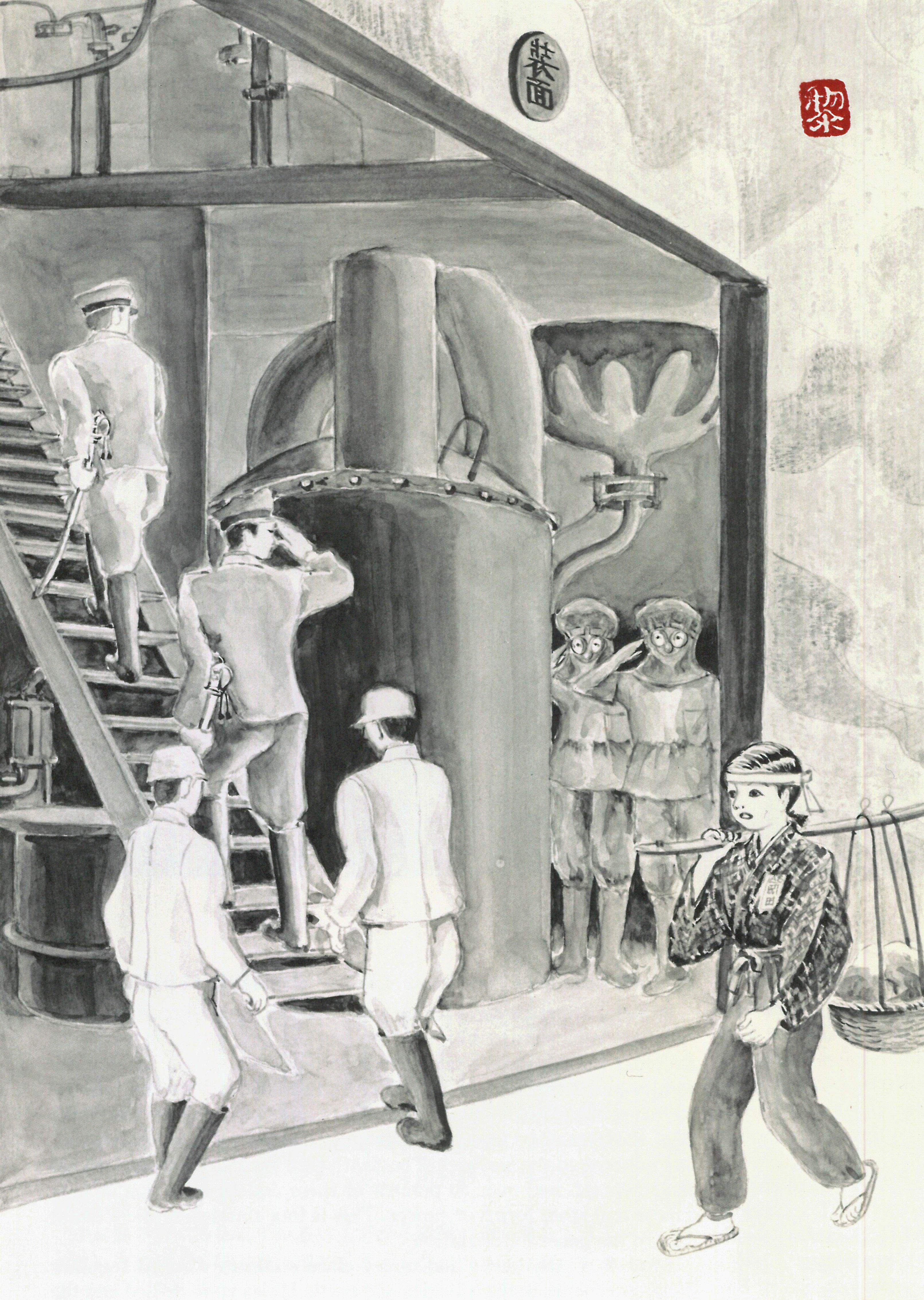

Reiko Okada's painting depicting mobilized students manufacturing "balloon bombs" (Courtesy of Reiko Okada)

Reiko Okada's painting depicting mobilized students manufacturing "balloon bombs" (Courtesy of Reiko Okada)

Carrying incendiary bombs and an advanced-for-its-time altitude control system, the balloons were able to ride the jet stream across the Pacific and reach North America.

Between 1944 and 1945, more than 9,000 of these balloons were launched, mostly from three bases in Japan, and at least 300 are believed to have reached the U.S. mainland, where they caused wildfires but little other major damage.

Okada realized her own culpability in the war, however, when she later learned that six people, including children, had been killed by a balloon bomb in western Oregon in May 1945 -- the only known casualties in the continental United States from an enemy attack during the war.

A balloon bomb drifting across North America, in July 1945. (AP/Kyodo)

A balloon bomb drifting across North America, in July 1945. (AP/Kyodo)

After the war, Okada studied at a fine arts college run by Kyoto city. She returned to her hometown of Mihara, where she taught art at a local high school until her mid-50s, before devoting herself to painting privately and peace work.

She suffered physical after-effects from her time in Hiroshima shortly after the bombing and from chronic bronchitis caused by her stint on Okunoshima. However, treatment allowed her to overcome her ailments.

After the war, Okada also learned that poison gas weapons had wreaked havoc in China. In 1989, after retiring from teaching, she published a book of pictures documenting her war experiences and sent it to Chinese war victims to express her remorse and apologies. Since then, she has continued her anti-war campaigning through her drawing and writing.

According to the U.S. military's post-war records, Japan produced 6,616 tons of poison gas that was used in over 7 million ammunition rounds, including artillery shells.

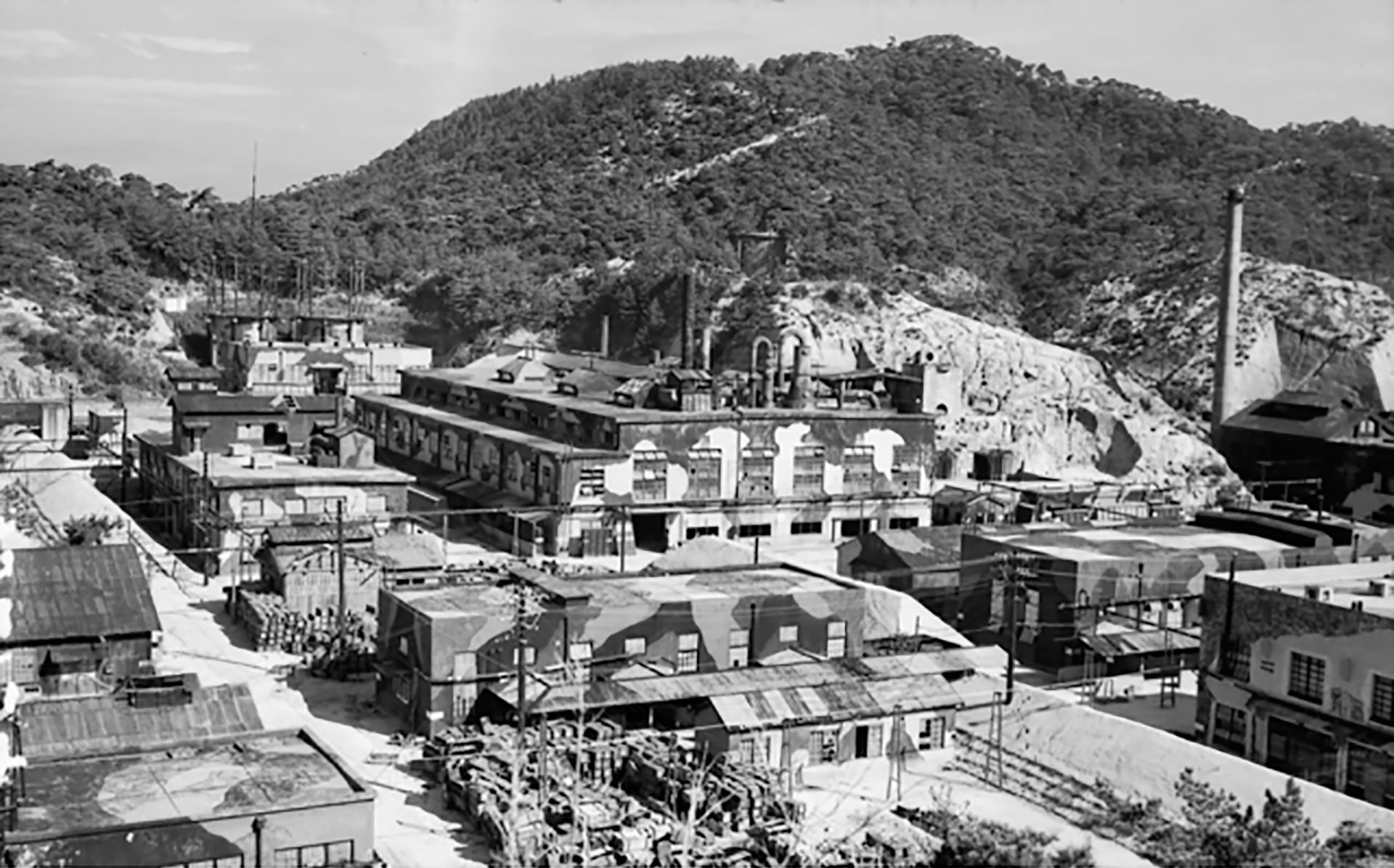

A group of factories on Okunoshima island, photographed in 1946 after the war. (Courtesy of the Australian War Memorial)

A group of factories on Okunoshima island, photographed in 1946 after the war. (Courtesy of the Australian War Memorial)

Some of the poison gas munitions transported to China went unused and were left abandoned, causing problems when they were later found or unearthed.

The Japanese government confirmed the "existence of abandoned chemical weapons" in a memorandum to the Chinese government in 1999.

A Japanese government investigation team conducts a preliminary survey of abandoned chemical weapons (poison gas shells) left behind by the former Japanese army in the suburbs of Dunhua, Jilin Province, northeastern China, in May 1996. (Courtesy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

A Japanese government investigation team conducts a preliminary survey of abandoned chemical weapons (poison gas shells) left behind by the former Japanese army in the suburbs of Dunhua, Jilin Province, northeastern China, in May 1996. (Courtesy of the Ministry of Foreign Affairs)

Currently, the total number of chemical weapon munitions left behind is estimated at more than 100,000. Japan and China are working together to dispose of them.

Okada believes Japanese people "should accept causing a war as our responsibility, face it, reflect on it, apologize for it, make amends for it and ensure that it leads to friendship and peace."

With various conflicts raging around the world, "we don't know when Japan will go to war," she said. "Each and every one of us must not be deceived, and we must all work together to prevent war."

"Nationalism is the doctrine that must be feared the most."

Other Spotlight Japan Stories

Matcha's moment in peril as Trump tariff threat looms over industry

Abreeze carries murmurs and quiet laughter between the rows of bright green tea leaves that are growing in dappled shade as workers harvest the plants that are destined to become matcha.

Remote Japan island, population 11, aims to become global manga hub

Visitors to Takaikamishima, in western Japan, are welcomed by a colorful cast of characters from Japanese manga which far outnumber the island's 11 residents where a revitalization project is underway.

Subterranean defenses prepare Tokyo for worst-case flood extremes

After visitors descend stairs winding 50 meters below ground, they emerge to an otherworldly sight -- a cavernous, dimly lit space with towering pillars reminiscent of a temple in ancient Rome.

The way of Sake

The addition of the traditional knowledge and skills used in sake-brewing to UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage List highlighted an industry facing shrinking consumption in Japan, but eyeing growing interest abroad, and possibly beyond.

The Company uses Google Analytics, an access analysis tool provided by Google. Google Analytics uses cookies to track use of the Service. (Client ID / IP address / Viewing page URL / Referrer / Device type / Operating system / Browser type / Language /Screen resolution) Users can prevent Google Analytics, as used by the Company, from tracking their use of the Service by downloading and installing the Google Analytics opt-out add-on provided by Google, and changing the add-on settings on their browser. (https://tools.google.com/dlpage/gaoptout) For more information about how Google handles collected data: Google Analytics Terms of Service (https://policies.google.com/technologies/cookies?hl=en#types-of-cookies) Google Privacy & Terms(https://policies.google.com/privacy)

© Kyodo News. All Rights Reserved. No reproduction or republication without written permission.