The addition of the traditional knowledge and skills used in sake-brewing to UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage List highlighted an industry facing shrinking consumption in Japan, but eyeing growing interest abroad, and possibly beyond.

Yamaguchi-based brewer Asahi Shuzo Co. is pursuing a dream of brewing sake on the Moon.

Inspired by efforts to establish a sustainable human presence on the Moon, the brewer known for its Dassai sake brand wants the eventual inhabitants to be able to enjoy a low-gravity tipple.

Japan's experiment module Kibo on the International Space Station in 2018. (Courtesy of JAXA/NASA)

Japan's experiment module Kibo on the International Space Station in 2018. (Courtesy of JAXA/NASA)

Before any lunar endeavor, Asahi Shuzo will attempt to brew sake on the International Space Station where equipment will recreate the gravity of the Moon's surface.

If successful, the sake will be presented as Dassai Moon, with the 100-milliliter bottle priced at 110 million yen ($738,000).

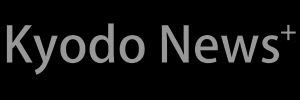

Speaking at an event in Tokyo in February, Japanese astronaut Soichi Noguchi said that he and other astronauts were excited by Asahi Shuzo's endeavor. "Until now, we were just taking something into space. Now they are actually going to make sake in space, which is a huge undertaking," he said.

Soichi Noguchi works on board the International Space Station in 2021. (Courtesy of NASA)

Soichi Noguchi works on board the International Space Station in 2021. (Courtesy of NASA)

Despite its grand vision, Asahi Shuzo maintains its roots at its headquarters in a remote corner of Yamaguchi Prefecture, in western Japan.

(Courtesy of Asahi Shuzo Co.)

(Courtesy of Asahi Shuzo Co.)

Inside the main brewing facility in Iwakuni, the company favors an approach of innovation over tradition. There is no veteran "toji," or master brewer. Instead, a young crew of brewers is largely focused on making junmai daiginjo sake. In the brewery’s analysis room, staff in lab coats carry out tests and analyze data.

"I think it is important not to make sake the same way it was a hundred years ago," Asahi Shuzo President and CEO Kazuhiro Sakurai said. "For us, making good sake means going beyond tradition. It means innovating and taking on new challenges."

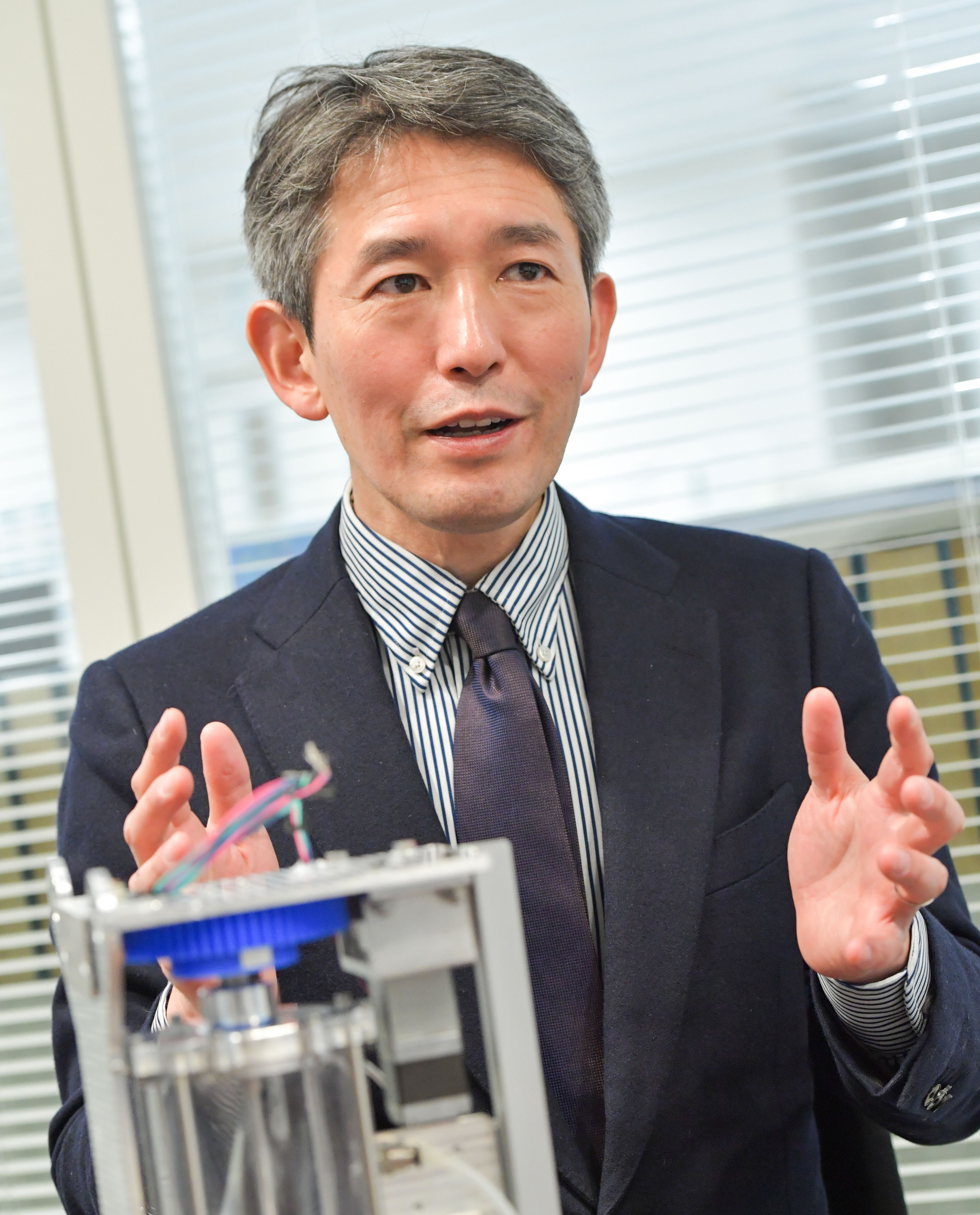

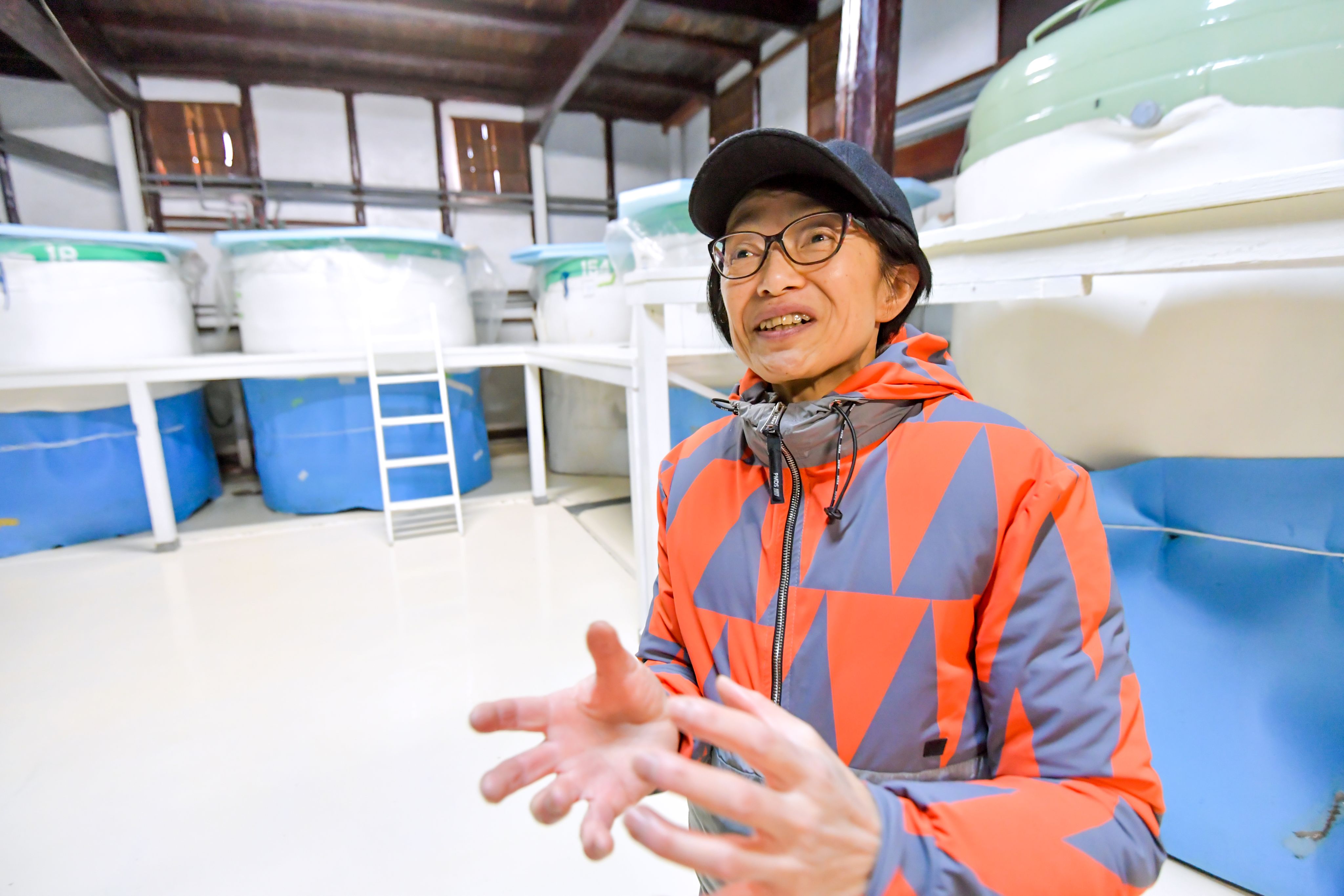

Kazuhiro Sakurai, president and CEO of Asahi Shuzo Co., shows the equipment that will be used for sake-brewing on board the International Space Station.

Kazuhiro Sakurai, president and CEO of Asahi Shuzo Co., shows the equipment that will be used for sake-brewing on board the International Space Station.

Even with all the data and innovation though, there are elements of sake-brewing at Asahi Shuzo that still demand the human touch.

Inside the koji muro, the work of separating rice grains is hot, sweaty and hands-on. In the fermentation room, staff plunge poles deep into tanks to stir the sake mash within, and in doing so release fruity aromas.

At the end of the brewing process, it all comes down to taste. The president and others gather to sample the pressed sake. Objectivity is key in judging whether or not it can be shipped.

Increasingly, Japan’s sake brewers are shipping their brews to consumers abroad.

At Imada Sake Brewing Co., in Hiroshima Prefecture, around 30 percent of sales of its Fukucho brand come from exports. From the quiet port town of Akitsu, facing the Seto Inland Sea, family-run Imada Shuzo sends its sake to around 20 countries.

Its Seafood brew has proven popular. Master brewer Miho Imada took a different approach to creating the sake. Starting with a brew to complement oysters, for which the waters around Akitsu are an ideal harvesting ground, the result is a lighter sake which the brewery ships to nearly all of its export countries.

Miho Imada works at her family's sake-brewing facility in Akitsu, Hiroshima Prefecture. (Courtesy of Kosuke Mae)

Miho Imada works at her family's sake-brewing facility in Akitsu, Hiroshima Prefecture. (Courtesy of Kosuke Mae)

There are hurdles to exporting, however. Longer periods of storage and transportation times can compromise the quality of sake, which deteriorates more easily than beverages like wine or whiskey.

To address that problem, Imada Shuzo has been brewing and exporting some of its sake with an improved yeast developed by Hiroshima Prefecture's Food Industry Technology Center. Developers described the refreshing acidity and fruity aroma of the resulting sake as one that would surprise even wine connoisseurs.

The brewing facility that Imada's family established in 1868 is a short walk from the sea. Behind the storehouse, mountains rise sharply. The brewery's landmark red-brick chimney remains from when coal was used in rice-steaming. "When people were looking for liquor stores in town, they would look for this kind of chimney and know there was a sake brewery here," Imada said.

They might not have come looking were it not for the efforts of Akitsu born brewer, Senzaburo Miura.

In the late 19th century, Miura developed a low-temperature brewing method capable of producing good sake from the area’s unusually soft water.

Imada often directs visitors to Sakakiyama Hachiman Shrine, where a bronze statue of Miura stands among stone sake barrels and other tributes from brewers to the shrine.

A statue of Senzaburo Miura stands in the grounds of Sakakiyama Hachiman Shrine.

A statue of Senzaburo Miura stands in the grounds of Sakakiyama Hachiman Shrine.

Imada said she likes to highlight the environment and the efforts of the brewers that brought the production of sake to its recent UNESCO heritage listing.

A small shrine within the grounds of Sakakiyama Hachiman Shrine is dedicated to a guardian deity of sake-brewing.

A small shrine within the grounds of Sakakiyama Hachiman Shrine is dedicated to a guardian deity of sake-brewing.

“I think it’s important for people to know why we use certain tools, how we see things, and how we feel, so they can become aware of what is good about Japanese people and about Japan,” she said.

While interest in sake is increasing abroad, in Japan the industry faces a crisis with consumption falling. In 2022, it had dropped to less than a third of its peak in the early 1970s, according to data from the National Tax Agency.

The country's oldest sake brand Kenbishi, however, remains unbending in its commitment to the old ways, seeing it as the best guarantor of quality.

Masataka Shirakashi, president of Kenbishi Sake Brewing Co., hopes the UNESCO heritage listing will encourage a revival of the beverage among drinkers in Japan.

In a workshop at Kenbishi's brewing facility in the western city of Kobe, a craftsman circles a barrel made of cedar. Using a wooden block and mallet, he hammers into place a bamboo hoop around it.

The craftsman is making a "dakidaru," which will be filled with boiling water and plunged into a tank to control the temperature of the yeast starter mix contained within by allowing heat to be released slowly

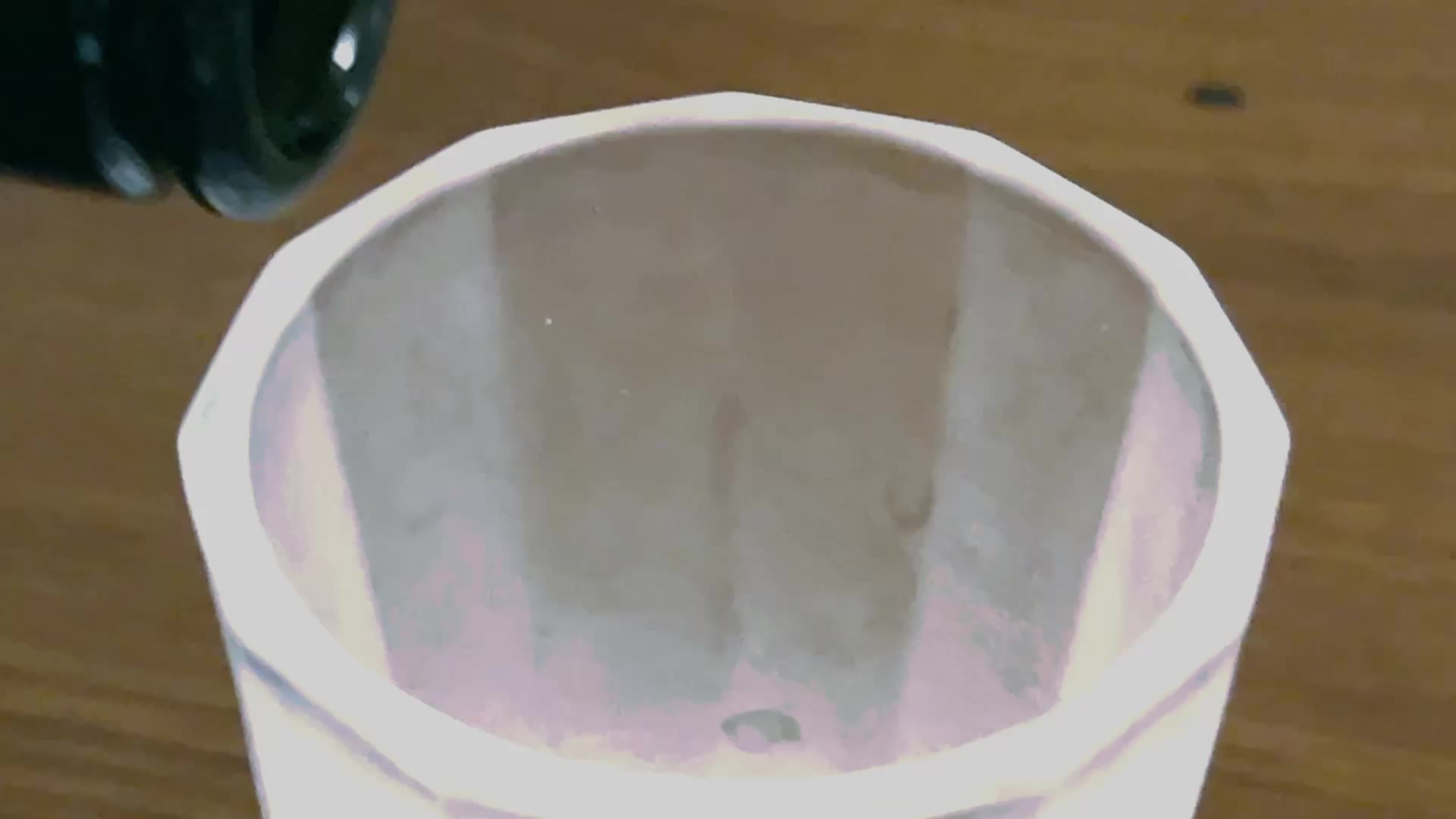

Masataka Shirakashi, president of Kenbishi Sake Brewing Co., explains the role of the "dakidaru" in sake-brewing.

Masataka Shirakashi, president of Kenbishi Sake Brewing Co., explains the role of the "dakidaru" in sake-brewing.

A team of three craftsmen makes around 30 dakidaru a year. After each use the barrel's six "taga," or bamboo hoops, need replacing. There are 300 dakidaru in circulation at the brewery.

Photo shows part of an impression of sake-brewing from the book “Nihon sankai meisan zue,” a guide to Japanese products first published in 1799. (Courtesy of the National Institute of Japanese Literature)

Photo shows part of an impression of sake-brewing from the book “Nihon sankai meisan zue,” a guide to Japanese products first published in 1799. (Courtesy of the National Institute of Japanese Literature)

"Maintenance is a hassle so fewer sake makers are using them," said Shirakashi, who has no qualms bucking this trend. "It's something you'd usually see in a museum."

The dakidaru is just one of the traditional wooden sake-brewing tools and pieces of equipment which Shirakashi said are needed to ensure the taste of Kenbishi's sake remains unchanged.

Kenbishi began making its own traditional wooden equipment in 2009, after dwindling demand made it hard to come by. Doing so comes at greater financial cost. But given its status as Japan's oldest sake brand, Shirakashi said, he feels a greater responsibility to protect it and maintain the taste of Kenbishi sake.

“If we give up on the taste, the brewing methods, and the tools and equipment, Japan will lose all of these things,” he said.

Kenbishi says it was founded sometime before 1505 in Itami, Hyogo Prefecture. During the Edo period (1603-1868), the brewery's sake was favored by samurai. According to the brewer, in 1740, it became an official supplier of sake to the shogun.

The Shirakashi family is the fifth to have headed Kenbishi. Despite changes in name and location, the company logo has remained unchanged for over 500 years.

The Kenbishi logo can be seen on a barrel in an impression of a scene from "The Fifty-Three Stations of the Tokaido" (Reisho version) by Utagawa Hiroshige (1797-1858). (Courtesy of Kenbishi Sake Brewing Co.)

Shirakashi follows the policy of his great-grandfather who believed that chasing after trends would always leave the company one step behind. Instead, Kenbishi should be like a stopped clock, always giving the right time twice a day.

"The trends will come back around, so we believe in the sake that our customers have said is delicious," Shirakashi said.

Read the full articles of this three-part series on Japan's sake brewers on Spotlight Japan:

>>>Part one: Innovation over tradition sending Dassai sake to the Moon

>>>Part two: Sake's export boom bringing in new fans and food pairings

>>>Part three: Japan's oldest sake brand determined to keep taste unchanged

Text : Tom Shuttleworth

Photo : Yuki Murayama

Video : Tom Shuttleworth

Text editors : David Hueston, Mark Smith, Tim Hornyak

Production Support : Kevin Chow, Janice Tang

Title image photos courtesy of Kenbishi Sake Brewing Co. and Asahi Shuzo Co.

Other Spotlight Japan Stories

Subterranean defenses prepare Tokyo for worst-case flood extremes

After visitors descend stairs winding 50 meters below ground, they emerge to an otherworldly sight -- a cavernous, dimly lit space with towering pillars reminiscent of a temple in ancient Rome.

Japan's unstaffed train stations getting rural revival on track

With rural Japan experiencing severe depopulation, some unstaffed train stations and vacant homes are being transformed into places for tourists to stay -- and it is proving a success.

Kinugawa Onsen reversing "haikyo" image amid foreign visitor boom

On the banks of Kinugawa River, a row of abandoned, crumbling hotels stands like a relic of a forgotten past. A destination that once thrived as a hot spring resort during Japan's bubble economy era of the 1980s, many parts of Kinugawa Onsen have now fallen silent.

Ramen bowls become canvas for art

Visitors to a ramen-themed exhibition in Tokyo are served a feast for the eyes with organizers inviting them to view one of Japan’s favorite dishes from the perspective of its bowl.

The Company uses Google Analytics, an access analysis tool provided by Google. Google Analytics uses cookies to track use of the Service. (Client ID / IP address / Viewing page URL / Referrer / Device type / Operating system / Browser type / Language /Screen resolution) Users can prevent Google Analytics, as used by the Company, from tracking their use of the Service by downloading and installing the Google Analytics opt-out add-on provided by Google, and changing the add-on settings on their browser. (https://tools.google.com/dlpage/gaoptout) For more information about how Google handles collected data: Google Analytics Terms of Service (https://policies.google.com/technologies/cookies?hl=en#types-of-cookies) Google Privacy & Terms(https://policies.google.com/privacy)

© Kyodo News. All Rights Reserved. No reproduction or republication without written permission.