Discarded chemical weapons materials from war torment residents over time

At the beginning of 2002, unusual symptoms appeared in Ryuji, a 6-month-old boy living in a small town in Ibaraki Prefecture north of Tokyo. The infant could not sit up or eat properly. With a high fever and trembling hands, he was diagnosed with an unknown cause of cerebral palsy.

Ryuji's family had moved into a rental house in Kamisu in October 2001. However, immediately after moving in, all four members of the family began to experience unexplained physical ailments.

Photo shows Ryuji Aotsuka around the time his family moved to Kamisu, Ibaraki Prefecture, in 2001. (Photo courtesy of Miyuki Aotsuka)

Photo shows Ryuji Aotsuka around the time his family moved to Kamisu, Ibaraki Prefecture, in 2001. (Photo courtesy of Miyuki Aotsuka)

"I remember that residents, including my family, were advised not to use the water because hazardous substances had been detected," said Ryuji's mother, Miyuki Aotsuka, 48. Ryuji's older sister Rina also began feeling ill and could not attend school, his mother said.

"The local police came to our house around 10 p.m. They had received a call reporting arsenic poisoning from the nearby water. The police asked me about the arsenic as if I were a suspect in an alleged poisoning of the water supply," said Ryuji's father Shinichi.

He said he later learned from news reports that the arsenic had leaked from a site where it had been dumped after originally being produced for use in the former Imperial Japanese Army's poison gas program.

In what is known as the Kamisu Arsenic Case, poison leaking from the buried chemicals contaminated the surrounding well water. Nearby residents who ingested the water experienced neurological symptoms such as numbness, dizziness and tremors in their limbs.

Ryuji was the most seriously affected. He suffered frequent seizures, and doctors told his parents that he might never walk. Even now, at age 24, he has severe disabilities, including delayed mental development. The poison gas ingredients, dumped in the area after World War II, ended up causing untold suffering to area residents decades later.

Photo shows Ryuji Aotsuka and his parents Miyuki(L) and Shinichi(R) around the time he began to develop worrying symptoms (Photo courtesy of Miyuki Aotsuka)

Photo shows Ryuji Aotsuka and his parents Miyuki(L) and Shinichi(R) around the time he began to develop worrying symptoms (Photo courtesy of Miyuki Aotsuka)

Referring to Ryuji, Miyuki said, "I had been feeding him skim milk mixed with well water, just like everyone else. Who could have imagined the water was contaminated?"

A view of Okunoshima Island taken on June 19, 2025.

A view of Okunoshima Island taken on June 19, 2025.

Japan produced chemical weapons during the war at a secret poison gas factory on Okunoshima, a remote island in Hiroshima Prefecture. Now famous globally as the photogenic "Rabbit Island," Okunoshima is nearly 900 kilometers away from Kamisu.

Photo taken in 1946 shows workers engaged in discarding poison gas at the former Japanese military's poison gas production facility on Okunoshima Island.

Photo taken in 1946 shows workers engaged in discarding poison gas at the former Japanese military's poison gas production facility on Okunoshima Island.

A view of central Kamisu City on Aug. 2, 2025, with the Kashima Coastal Industrial Zone stretching along the coastline.

A view of central Kamisu City on Aug. 2, 2025, with the Kashima Coastal Industrial Zone stretching along the coastline.

However, the people who were responsible for the dumping are still unknown. The fact that the victims have no outlet to express their anger, even after the prefectural government paid settlement money and the Japanese government covered medical expenses, further torments them psychologically.

Workers in protective suits and dust masks prepare to excavate a site contaminated with high concentrations of arsenic in Kamisu, Ibaraki Prefecture, in December 2024. (Kyodo)

Workers in protective suits and dust masks prepare to excavate a site contaminated with high concentrations of arsenic in Kamisu, Ibaraki Prefecture, in December 2024. (Kyodo)

"When symptoms appeared in my son Ryuji, I didn't know who or what to blame. Why did it happen?" Miyuki asks today.

Ryuji, who eventually learned to walk, still lives with his parents and has never been independent. He attended special needs schools from elementary to high school. A care worker regularly visits him to play cards and give him a health check-up.

Watching soccer is his passion. Growing up in a town close to where the Kashima Antlers, a major force in domestic soccer, are based, Ryuji played the sport for six years in middle school. "I'm still amazed that he can run and play soccer, since doctors told me he would never walk," said Shinichi.

(Photo courtesy of Miyuki Aotsuka)

(Photo courtesy of Miyuki Aotsuka)

The Aotsuka family is especially grateful to Tsuyoshi Ogata, head of the local health center, for researching the water supply and helping residents apply for a special medication book that allows them to receive free medical care.

Ogata was assigned to the Itako Health Center in 2003 amid residents' concerns about the water. A University of Tokyo medical school graduate, Ogata had been working on Minamata disease, the neurological syndrome caused by major industrial pollution in Minamata, Kumamoto Prefecture.

"Several residents were experiencing unusual symptoms. I thought the problem was water, like the Minamata case I was familiar with. History sometimes repeats itself, so I was grateful to learn lessons from the past," Ogata said. He added that there was no distinct department handling health injuries from underground water since it was a natural resource.

Photo shows a concrete object found at the area where a high level of arsenic was detected. (Photo courtesy of the Japanese Ministry of the Environment)

Photo shows a concrete object found at the area where a high level of arsenic was detected. (Photo courtesy of the Japanese Ministry of the Environment)

"I knew someone had to work on this, even if it may be outside our jurisdiction," Ogata added.

A water quality survey found that arsenic levels in the well water that the family used for drinking were 450 times higher than the environmental standard.

Photo taken in 2003 shows pumps that drew water from the well near the Aotsuka family's former residence. (Photo courtesy of Itako Health Center)

Photo taken in 2003 shows pumps that drew water from the well near the Aotsuka family's former residence. (Photo courtesy of Itako Health Center)

Analysis revealed the poison to be an organic arsenic compound, specifically diphenylarsenic acid, which does not exist in nature. Further investigation revealed that diphenylarsenic acid had been buried in concrete in an empty lot approximately 90 meters from Aotsuka's home.

In July 2006, Kamisu residents sued the Japanese government and Ibaraki Prefecture, seeking damages for those who ingested the contaminated water. The action was taken through a pollution research commission for damage caused by industrial pollution nationwide.

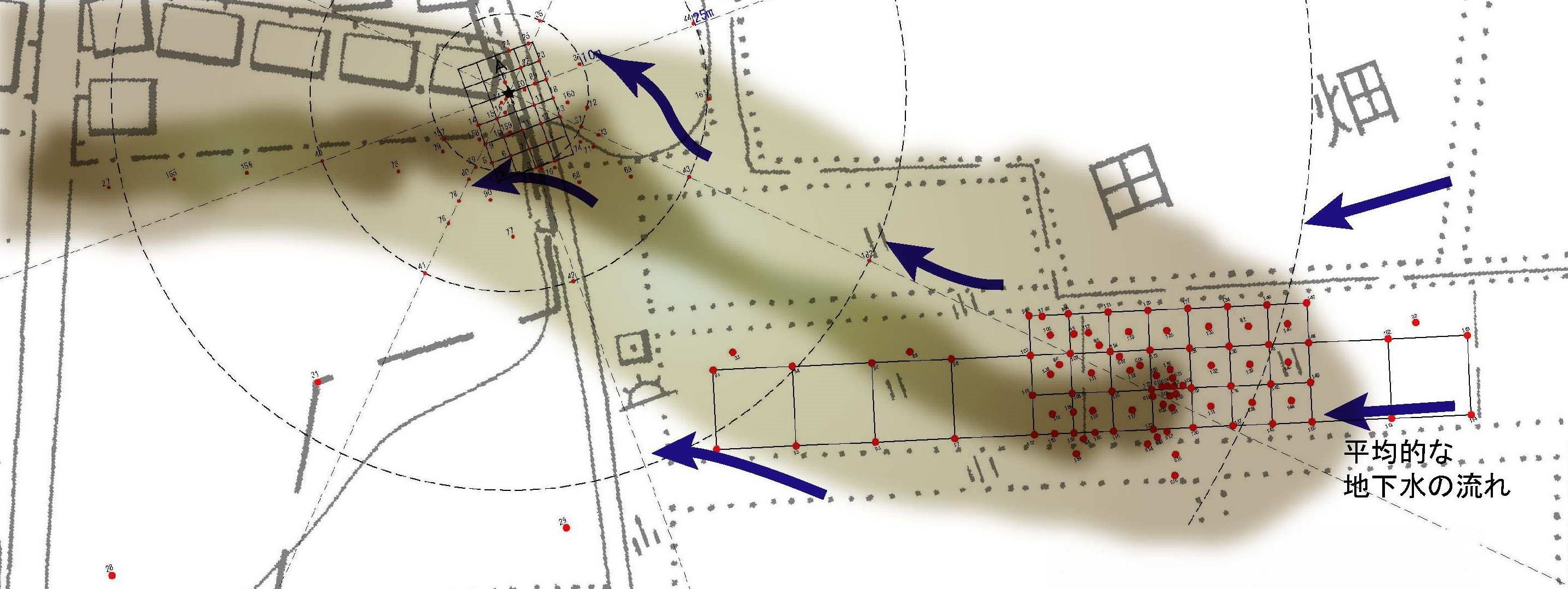

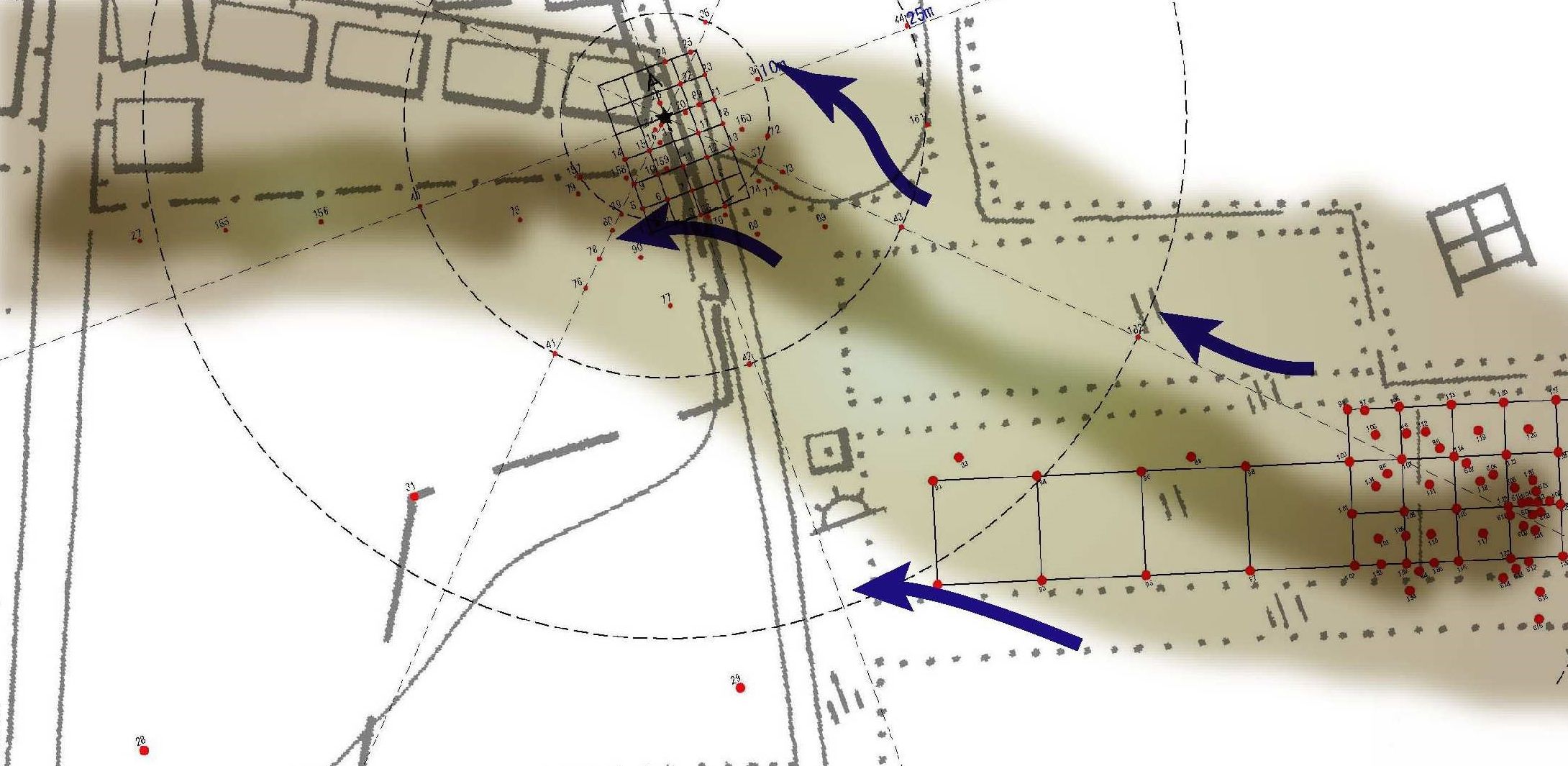

Photo of a deep groundwater contamination map from the pollution source to the area surrounding the rented house where the Aotsuka family lived at the time. (Photo courtesy of the Japanese Ministry of the Environment)

Photo of a deep groundwater contamination map from the pollution source to the area surrounding the rented house where the Aotsuka family lived at the time. (Photo courtesy of the Japanese Ministry of the Environment)

In 2012, the national Environmental Dispute Coordination Commission decided the prefecture should pay for the care of patients, including Ryuji. It also concluded that the prefecture made an inappropriate decision to label the arsenic as "naturally derived" and failed to conduct a sufficient investigation into where the arsenic came from.

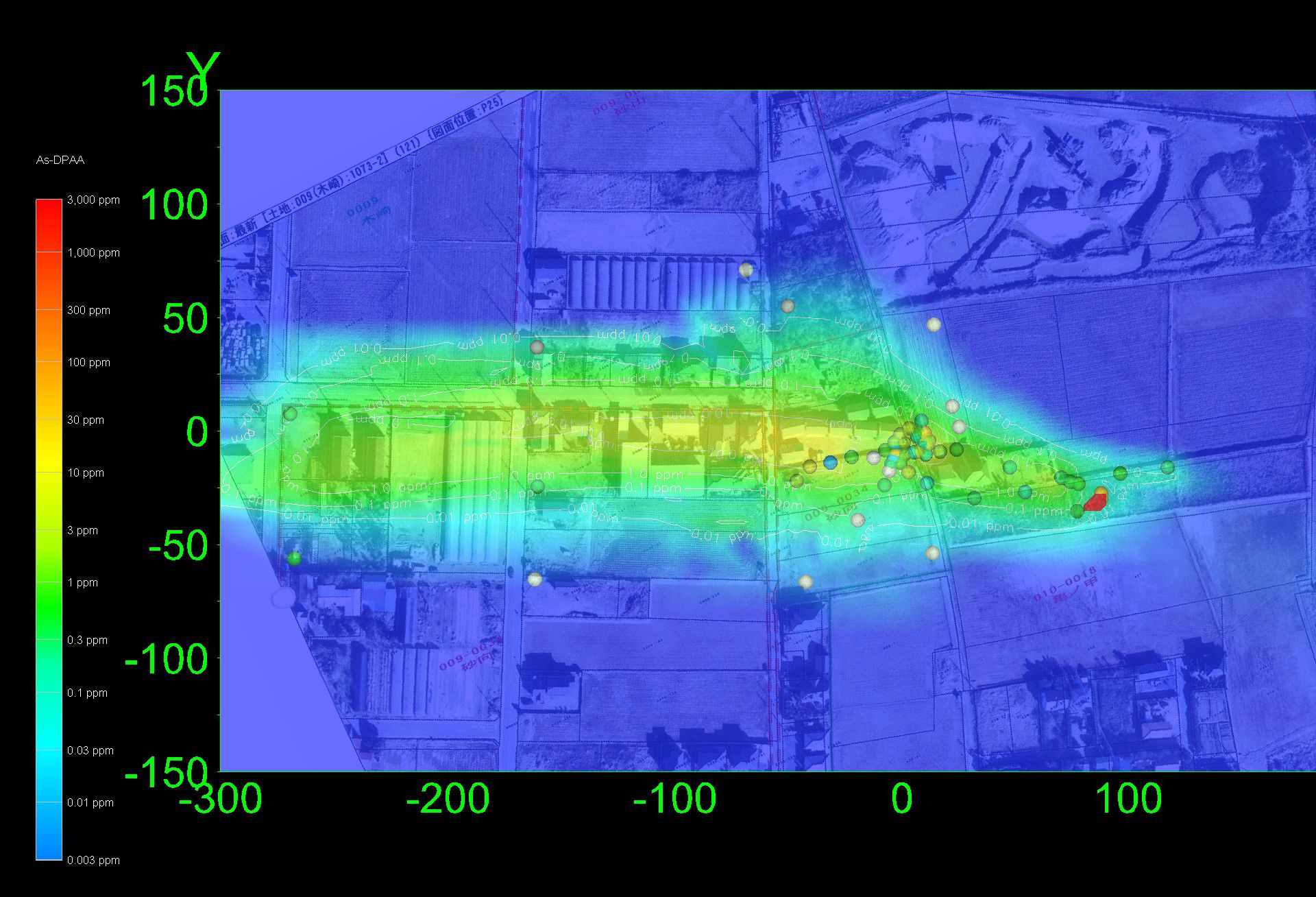

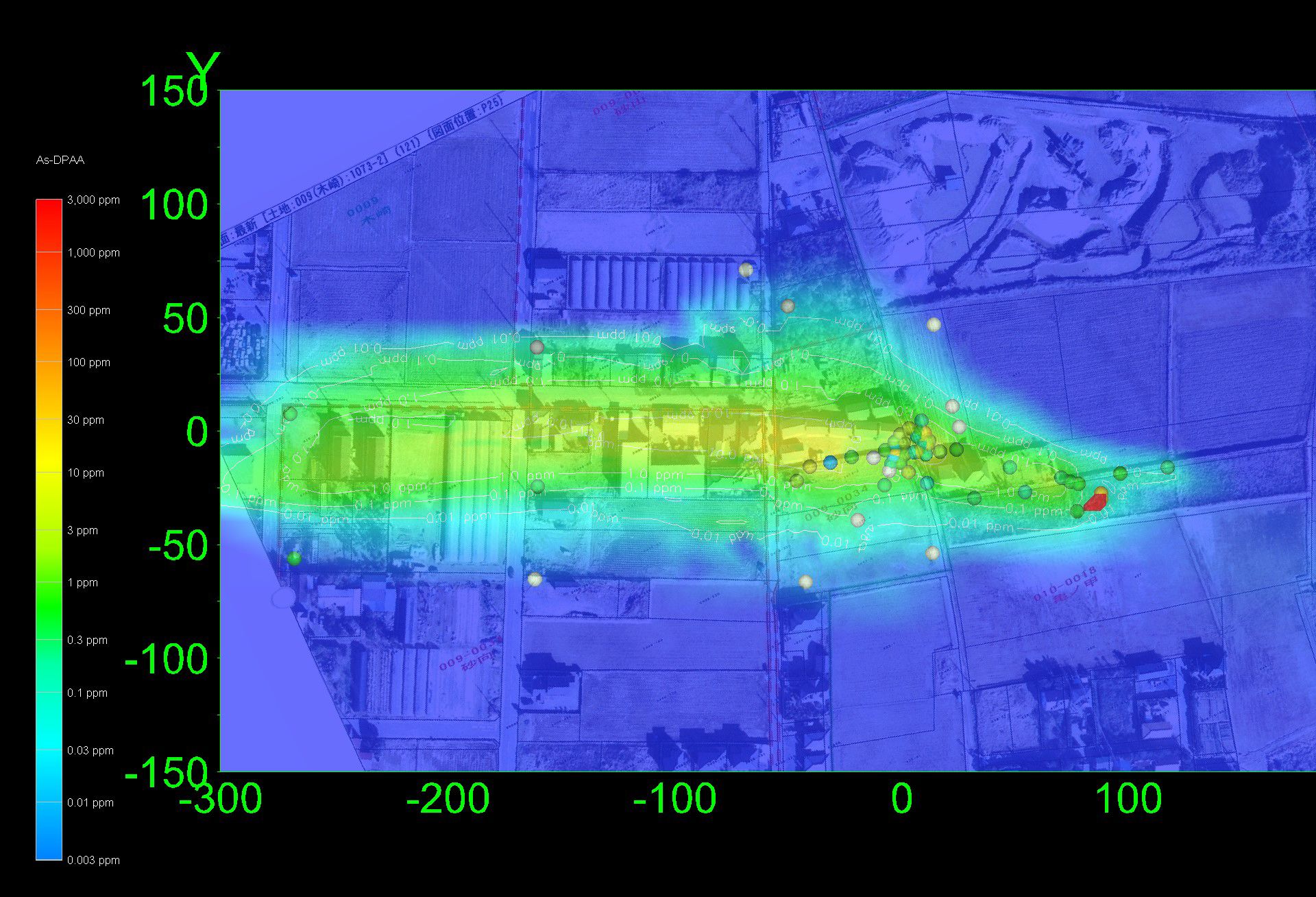

Photo of a map showing the concentration distribution from the pollution source to the vicinity of the rented house where the Aotsuka family lived at the time, based on groundwater contamination simulation depth 30 meters.(Photo courtesy of the Japanese Ministry of the Environment)

Photo of a map showing the concentration distribution from the pollution source to the vicinity of the rented house where the Aotsuka family lived at the time, based on groundwater contamination simulation depth 30 meters.(Photo courtesy of the Japanese Ministry of the Environment)

However, the commission didn't blame the government for neglecting its duty to properly manage the substance -- a key claim by the residents.

Miyuki said, "I refused to sign the reconciliation document until I was the last one not to do so, but I gave up filing a lawsuit with the top court because it would have just dragged on and got harder. I already felt I'd accomplished something fighting for almost 10 years."

"I have been feeling responsible for taking care of Ryuji because I'm the first child. I changed jobs from working at a convenience store to being a care worker to learn how to take care of disabled people. I have been doing that for three years now," said Ryuji's sister Rina, 30.

Although times have been difficult, Shinichi has grown to accept his son's condition.

"What I am looking for is to travel a lot and watch football games with him for as long as I can."

"Sometimes I blame myself for feeding my children contaminated water," said Miyuki. "I blame the war for causing us indirect suffering, which is completely unfair. However, I have made up my mind to be positive, and we are happy as we are. I love my son Ryuji."

※Back ground photo courtesy of Miyuki Aotsuka

Other Spotlight Japan Stories

Japanese underground idol culture booming in China

At a club in Shanghai, dozens of young people jump and wave glow sticks as they dance to the music. They're Chinese amateur girl groups singing in Japanese, and this is Japan's globalized idol culture.

Distillery mixes funky beats into brown sugar shochu

Okunoshima has become famous globally as Japan's Instagrammable "Rabbit Island" but little is known about its dark history as a host to a wartime poison gas factory and weapons plant.

Wartime child worker reveals dark secrets of Japan's "Rabbit Island"

Okunoshima has become famous globally as Japan's Instagrammable "Rabbit Island" but little is known about its dark history as a host to a wartime poison gas factory and weapons plant.

Revival of revered Mt. Fuji trail

putting spirit back into climb

Gripped by summit fever, many Mt. Fuji climbers head straight to the mountain’s 5th stations to pick up trails to the top, leaving a once revered route largely forgotten.

The Company uses Google Analytics, an access analysis tool provided by Google. Google Analytics uses cookies to track use of the Service. (Client ID / IP address / Viewing page URL / Referrer / Device type / Operating system / Browser type / Language /Screen resolution) Users can prevent Google Analytics, as used by the Company, from tracking their use of the Service by downloading and installing the Google Analytics opt-out add-on provided by Google, and changing the add-on settings on their browser. (https://tools.google.com/dlpage/gaoptout) For more information about how Google handles collected data: Google Analytics Terms of Service (https://policies.google.com/technologies/cookies?hl=en#types-of-cookies) Google Privacy & Terms(https://policies.google.com/privacy)

© Kyodo News. All Rights Reserved. No reproduction or republication without written permission.