It’s a testament to the enduring appeal of surfing that despite facing the adversity of a tsunami and nuclear disaster a beach community in Fukushima is revitalizing the region through surf tourism.

The beach at Kitaizumi, in the city of Minamisoma, offers some of the most consistent surf to be found anywhere in Japan. Local surfers and community leaders are using the almost year-round supply of waves to drive a so-called surf tourism initiative to revitalize the city through marine leisure.

©︎KITAIZUMI SURF FESTIVAL 2024

©︎KITAIZUMI SURF FESTIVAL 2024

In early October, surfers from around Japan came to Minamisoma to compete during the Kitaizumi Surf Festival. The event took place just over a year after the government began releasing treated water from the crippled Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant into the ocean, less than 30km away.

Turning point

The festival was intended to mark a return to the area staging the kind of large contests and celebrations of the beach lifestyle that were being held prior to the earthquake and tsunami in March 2011.

While the inaugural festival in September 2023 took place amid fears surrounding the first release of the treated water the previous August, this year the contest field was more than doubled to around 160 athletes.

Among the festival guests was one of the most famous names in surfing, former world champion Joel Parkinson.

Former surfing world champion Joel Parkinson at Kitaizumi Surf Festival 2024.

Former surfing world champion Joel Parkinson at Kitaizumi Surf Festival 2024.

Parkinson, or “Parko” as the Australian is affectionately known, said he had enjoyed some fun surfs during the festival. The 2012 ASP World Champion also took some of the next generation of surfers through their paces during a surf school attended by local children, one of a program of events offered alongside the contest.

“Of course, there was the issue of the nuclear power plant, but we need to move on from that. Having overseas guests like Parko spread the word to the world about what a great place this is, is so important,” Shinji Murohara, chairman of the festival’s organizing body, said.

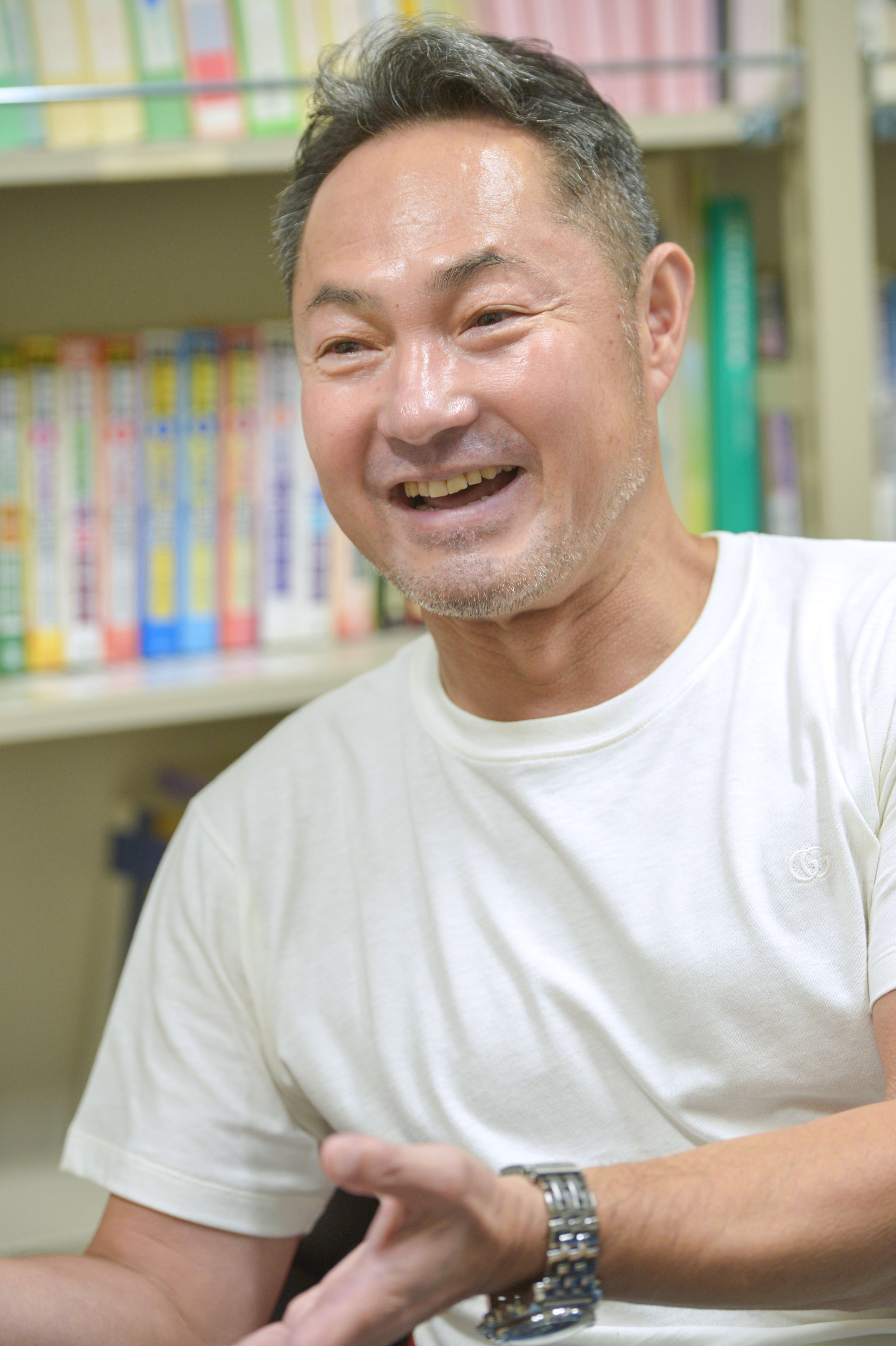

Shinji Murohara at Kitaizumi Festival 2024.

Shinji Murohara at Kitaizumi Festival 2024.

Murohara, a prominent local surfer, is one of the leading figures of surf tourism in Minamisoma. He believes the festival marked a turning point for the initiative.

“To a certain extent, the situation here has been communicated to the rest of Japan - that the area is safe, that more people are coming here,” he said. “Now it's time to tell the world that this area is safe.”

Background video : ©︎KITAIZUMI SURF FESTIVAL 2024

Realizing the ocean resource

Efforts to revitalize Minamisoma through surf tourism began around 20 years ago when surfer Hideki Okumoto first visited the area.

Hideki Okumoto at Fukushima University.

Hideki Okumoto at Fukushima University.

Okumoto, a professor at Fukushima University, was part of a committee charged with reviving manufacturing in the city after factories began leaving the area in the 1980s, taking jobs with them and leaving behind an aging population.

The professor’s attention, however, was drawn to the vibrant surfing scene at Kitaizumi which he felt presented a striking contrast to some of the gloomy data coming out of the city.

"Revitalizing manufacturing was a good thing, but the city had more to offer. The ocean,” Okumoto told Kyodo News Plus during the festival period.

Okumoto envisioned a town revitalized through the use of its ocean resource, with people moving to the area to enjoy life by the beach. Outside the world of surfing, Minamisoma is best known for the Soma Nomaoi festival, an annual military reenactment featuring a parade of samurai on horseback.

Soma Nomaoi festival. May 2024.

Soma Nomaoi festival. May 2024.

With the creation of the Minamisoma Surf Tourism Promotion Committee in 2003, Okumoto brought together local surfers, chambers of commerce, and tourism associations, among other organizations, to ensure that any resulting initiative would benefit the city as a whole, not just surfers.

The committee faced early opposition, according to Okumoto. Some of the area’s older residents, unfamiliar with surfing culture, were fearful of inviting surfers to the city who they took to be a bad influence. Meanwhile, local surfers were wary of their Kanto-based counterparts traveling further north to escape the crowded breaks of Chiba and Shonan.

With many local surfers having to leave the area in search of work, and quit surfing as a result, however, surf tourism aimed to create opportunities for them to stay and make their living by the beach.

Promoting and maintaining a safe beach environment was a priority for the initiative. Local surfers were employed as lifesavers with the city providing a budget to cover their salaries. Subsidies also came from the prefecture, to hold contests attracting surfers from all over Japan.

Surfing school at Kitaizumi Surf Festival 2024.

Surfing school at Kitaizumi Surf Festival 2024.

By 2010, contests were a regular fixture in Kitaizumi. For Okumoto and the city they were also an opportunity to show residents and visitors the different ways they could enjoy the beach environment year-round. In town, some restaurants and cafes were even offering free coffee and beer to the visiting surfers, according to Okumoto.

With the increase in surfers and repeat visitors to the city came an increase in support for surf tourism.

Going again

“After the disaster, when we were faced with starting again from scratch, people who had been opposed to the initiative at the beginning were encouraging us to try again a second time,” Okumoto said.

Surfing and surf tourism were put on hold though. Okumoto and other surfers stayed out of the water for a three-year period of mourning which they concluded with a Buddhist ceremony to mark the resting of the souls of the dead.

Odaka District, Minamisoma. March 12, 2011.

Odaka District, Minamisoma. March 12, 2011.

Across Minamisoma, over 1,100 lives were lost as a result of the disaster. Kitaizumi narrowly avoided an evacuation order that turned parts of the city into a no-go zone until 2016.

When competition returned it was with standup paddle boarding before momentum started to build with local amateur surfing contests through which the city could start to communicate once again the appeals of its ocean.

Minamisoma Memorial Park

Minamisoma Memorial Park

Despite the release of the treated water, Okumoto speculates that the number of surfers at Kitaizumi has now returned to something close to pre-disaster levels when conservative estimates placed the number at around 100,000 annually.

A balancing act

“Of course, as far as the treated water is concerned, I think there will be more rumors. Since the disaster though, we’ve had the mindset of believing in the science,” Okumoto said.

Matching the science with sensitivity to the public mood is one of the balancing acts facing leaders of surf tourism as they look to move forward.

Another involves government financial aid given to those whose livelihoods suffered due to the disaster. From city hall to the backseat of taxi cabs, debate lingers in the region about its efficacy. Some people suspect the aid has reduced appetites to work toward wider-reaching, longer-term community goals.

Okumoto remains enthusiastic about the potential of surf tourism though, and not just for Minamisoma. He hopes to establish the city as a model for others to follow. Doing so, he believes, will help to regenerate Japan’s coastline and beaches too often lost to concrete.

Legendary local surfer

When it comes to the waves in Minamisoma though, few people likely understand their enduring appeal better than local surfer Koji Suzuki.

Local surfer Koji Suzuki.

Local surfer Koji Suzuki.

At 69, Suzuki has been surfing in the area for around 50 years. Despite losing his home and his surf shop to the tsunami, he was back in the water just four months after the disaster.

“I thought that someone had to go surfing, otherwise how were we ever going to get it back?” Suzuki told Kyodo News Plus at his relocated surf shop in the city’s Kashima district.

Suzuki was among the organizers of the first all-Japan surfing contest to be held in the Tohoku region, over 30 years ago. He used his experience to help Okumoto get surf tourism up and running.

Koji Suzuki at his shop, Surf Shop Sun Marine, in Minamisoma.

Koji Suzuki at his shop, Surf Shop Sun Marine, in Minamisoma.

These days the veteran surfer said he prefers to take a backseat to event organization. He still surfs when there are waves though, which is most days in Minamisoma, and he remains a supporter of surf tourism.

“Developing the town through surfing might mean crowded waves, but I think it’s more fun for me to let people know about the ocean that I am so fond of, and have them come and surf with me,” Suzuki said.

This article was submitted by a contributing writer for publication on Kyodo News Plus.

More latest news from Japan on

The Company uses Google Analytics, an access analysis tool provided by Google. Google Analytics uses cookies to track use of the Service. (Client ID / IP address / Viewing page URL / Referrer / Device type / Operating system / Browser type / Language /Screen resolution) Users can prevent Google Analytics, as used by the Company, from tracking their use of the Service by downloading and installing the Google Analytics opt-out add-on provided by Google, and changing the add-on settings on their browser. (https://tools.google.com/dlpage/gaoptout) For more information about how Google handles collected data: Google Analytics Terms of Service (https://policies.google.com/technologies/cookies?hl=en#types-of-cookies) Google Privacy & Terms(https://policies.google.com/privacy)

© Kyodo News. All Rights Reserved. No reproduction or republication without written permission.